In the January edition of Edubytes, our guest editor is Dr. Jaclyn (Jackie) Stewart, the incoming director of the UBC Institute for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (ISoTL). In this edition, Jackie provides an introduction to the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL), equity, diversity, and inclusion in SoTL work, and how SoTL is well-positioned to understand the impacts of the pandemic on teaching and learning.

The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) is a process of improving student learning through systematic investigation of teaching practices. Often considered a ‘cycle of inquiry’, a SoTL practitioner defines questions, identifies the evidence and methods required to answer the questions, creates a plan, prepares measures or tools, collects and analyzes data, and identifies new question(s).

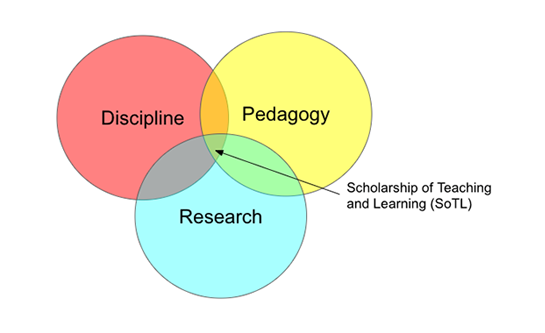

Many SoTL practitioners use the methodologies from the discipline of their research training; e.g., humanities methodologies to study learning in the humanities, or science/social science approaches to studying learning in the sciences. This is what makes SoTL special — the field of SoTL is a “big tent” for multiple perspectives, methodologies, and goals. We position SoTL at the nexus of disciplinary knowledge, pedagogical practice, and research, and consider SoTL an important bridge between teaching practice and research.

Image courtesy of UBC ISoTL

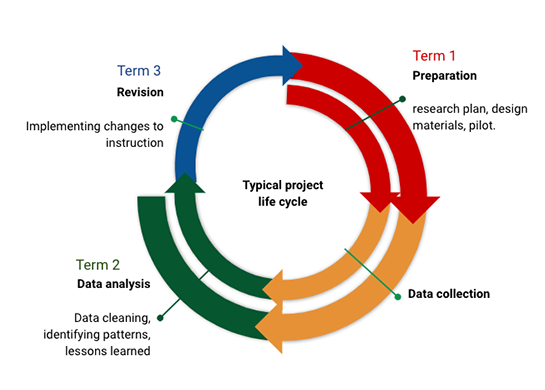

SoTL is a cyclical process that can produce new knowledge about higher education pedagogy — and because of its reflective qualities, it is also a form of professional development. For example, a SoTL approach to developing an evidence-based course activity would involve creating a first version of the activity based on the literature about how people learn and ideally student feedback, then collecting data to investigate students’ learning and perceptions of the activity, and making adjustments to the activity based on this new evidence. The revised activity and evidence supporting its use could then be shared with others. The cyclical nature of SoTL aligns with the iterative improvements people make to their courses, learning activities, and assessments. SoTL is a way to document changes and detect how changes to instruction impact students.

Image courtesy of UBC ISoTL

Getting started with SoTL

This article presents a straight-forward description of seven steps in a SoTL project. The steps mimic the process of scholarly investigation, and thus probably are familiar to many post-secondary educators. These ideas are elaborated in Peter Felton’s “Principles of Good Practice in SoTL” article, which provides suggestions for engaging students in the SoTL process and discusses the importance of connecting research questions with appropriate methods applied rigorously.

At UBC, the SoTL seed program is a fantastic way start a project with the support of a SoTL specialist.

Disseminating SoTL

Like any research, SoTL isn’t finished until it is shared. Sharing the results of the scholarly work can take many forms. Healey, Matthews, and Cook-Sather share strategies for SoTL dissemination through peer-reviewed journals.

Sharing SoTL work can be done through conversations with colleagues, publicly through one’s website, blog, or portfolio, or more traditionally at academic conferences and in journals. Curriculum and teaching activities which have been developed and improved through a SoTL process can be shared in repositories, some of which are peer reviewed. For getting started with publishing in SoTL journals, see slides for ISoTL’s workshop on SoTL journal publishing [PDF], and three tips for getting your SoTL manuscript published from the International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning.

Engaging students in SoTL

The movement of engaging students as peers in curriculum development, course design, teaching, or pedagogical research is known as ‘students as partners’, as explored in Edubytes July 2019. SoTL practitioners are increasingly involving students as partners, which places students’ experiences and values of the forefront of the work. This account of involving students as co-creators and co-investigators of an upper-level science course led to student growth and new inspiration for instructors.

Equity, diversity, and inclusion in SoTL

Our assumptions, and resulting actions, can unintentionally contribute to marginalization or inequities in our scholarly work. To bring a lens of equity, diversity, and inclusion to SoTL practice, we need to interrogate our research practices. Consider the relevance of information collected from students, how specific to be, and how to ask questions in inclusive ways. The UBC Equity and Inclusion Office has published guidelines for asking for demographic information (PDF), and ISoTL offers workshops on inclusive survey design (download the slides).

The emerging SoTL work from the last year has shown how well positioned SoTL practitioners have been to meet the teaching and learning needs of the pandemic. One of my favourite recent papers did this to uncover how instructors could increase engagement in their emergency remote courses.

SoTL is well positioned to assist educators with deciding how to design remote courses. The article, from CBE Life Sciences Education, describes the case of a learning community of equity-focussed educators who worked to increase the “participatory equity” in their classes following the switch to remote instruction last spring. By analyzing videos of face-to-face and online classes after the transition to remote instruction, they detected a 50% drop off in participation as measured by verbal ‘sequences’. Seven strategies led to participatory equity: “1) re-establishing norms, 2) using student names, 3) using breakout rooms, 4) leveraging chat-based participation, 5) using polling software, 6) creating an inclusive curriculum, and 7) cutting content to maintain rigor.”

A UBC study on how the switch to remote teaching last spring affected students’ wellbeing showed that 3/5 students preferred live online classes that are made available as recordings. Practices with particular positive impacts on student learning and wellbeing included using take-home examinations, and adjusting course grading schemes. Students’ wellbeing was supported when instructors provided choices and had flexible course policies.

Enjoyed reading about the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning? Learn about other topics we covered in the January 2021 edition by reading the complete Edubytes newsletter. To view past issues, visit the Edubytes archive.

Are you interested in staying up to date on the latest trends in teaching and learning in higher education? Sign up for our newsletter and get this content delivered to your inbox once a month.